Embrace is a team of six first-year students from the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University. Our team consists of Amber Griffith (2D Artist, Graphics Designer, Game Designer), Alexa Wang (UI/UX, Assistant Producer), Chao Li (Game Designer, Programmer), Jeffrey Liu (Lead Game Designer, Programmer), Shan Jiang (Lead Producer), Shicai He (Lead Programmer). Working with our client, Ayana Ledford, Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CMU), we are creating an interactive and collaborative live orientation experience for incoming students to Dietrich College to learn about cultural humility. Our deliverables include web-based activities, video demos, and a program guide. Download here.

The definition of cultural humility:

“A lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another’s culture, but starts with an examination of their own beliefs and cultural identities.”

“The overall purpose of the process is to be aware of our own values and beliefs that come from a combination of cultures in order to increase understanding of others.”

Yeager KA, Bauer-Wu S. Cultural humility: essential foundation for clinical researchers. Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26(4):251-256. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2013.06.008

The activity that we created is a group experience meant to teach the concept of cultural humility in a way that is introductory, interactive, and fun! The experience is designed to run in a large group setting, with a facilitator guided by the host program, ideally visible to all on a big screen, and participants using their own mobile devices to interact anonymously. Facilitators are welcome to participate as well with their own mobile devices if they wish. By the end of the program, participants are able to: identify attributes of their own cultural identity and rank their personal importance; share pieces of their identity with others as they feel comfortable; learn about others’ cultural identities while respecting others’ boundaries.

What went well

Building a product solution from scratch

In our first meeting with the client, we were able to identify the key aspects, including the definition of cultural humility, why is it important, the expected goals of the experience, the target audience, the expected project deliverables, and the expected length of the experience, etc. To read more about the answers, please refer to the production blog of week 2. Apart from AR/VR, we were not given restrictions on the delivery methods. For the following week, we debated whether we should create an interactive film or a multi-player game. The decision was made by our client to go for a game, considering the appearance of real actors/actresses in a film would keep the audience’s attention on their identities, such as races, hairstyles, clothes, and the way they perform. This could be hard for the audience to relate to themselves, after all, everyone is different and explicit representation could easily be outdated. The format of interactive films could also be just leading to an answer, instead of teaching students to reflect on the topic. Our designers were able to come up with 3 game ideas, including culture evolution, Q&A, and culture wheels, in the same week. The final winner turned out to be culture wheels because the first one was out of scope and the second one seemed plain.

Culture Wheel (Final version)

McConomy Auditorium

From this point on (week 4), we started to develop the full idea around culture wheels. We used culture wheels to symbolize cultural identity. Taking the large audience (300-400 incoming first-years) and limited auditorium space into account, an online web-based activity with a live facilitator was the best option for us. For our audience, we want to enable self-reflection on their own cultural aspects, show cultural diversity within the participants in an inclusive way, and encourage openness to understand others’ cultural aspects. Since the given timeframe (15 minutes) would be very limited to discuss such a serious topic in-depth, we negotiated with our client to only consider our activities as an introduction leading to the roundtable discussion afterward.

In the 15 minutes, we further divided the activities into 4 parts, consisting of 1) concept introduction, 2) building culture wheels, 3) seeking, and 4) wrap-up report. When they build their own cultural wheels, each wheel shows attributes in Music, Food, Hobbies, Finances, Home, and Ethnicity and their relative importance to themselves. During our multiple playtests, many commented that they reflected on their cultural identity and wanted to start a deeper conversation. Using their wheels, participants are brought together in a shared space to explore the cultural identities of the group because it is important to realize that building a community isn’t just being open to sharing parts of themselves, but also being open to learning about others.

We struggled in the development of the third part for the majority of the semester. Initially, the design was not a seeking activity, but a bucket activity, where players should go find a bucket that matches their identity. It did not receive positive feedback during playtesting as players didn’t understand what and why they were doing. However, we hesitated to replace it until week 12 (3 weeks before the semester ends) after we talked with Jessica Hammer. She is the Thomas and Lydia Moran Associate Professor of Learning Science, jointly appointed in the HCI Institute and the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University. Her research focuses on transformational games, which are games that change how players think, feel, or behave. She pointed out that we could create meaning and make the bucket something else that’s fun. We could also make everyone work towards a common polished goal and make it a timed competition. Once the consultation was over, our designers were able to come up with the seeking activity, where players search for someone with a specific identity to celebrate cultural diversity. The total score of correct identities found is displayed on the big screen so everyone could work towards a common goal. The new activity has a time restriction which involves a little competition in the collaboration. After 2 weeks of replacing this part, we received a 40% increase in players’ feedback on understanding the function and purpose of the activity.

Bucket Activity

Seeking Activity

The final part, the wrap-up report, summarizes the data during the activities. The big screen shows word clouds compiling the responses from all the participants from each of the attributes. Participants are shown their custom reports as well on their devices, including their score during the seeking part and how their identities relate to others in the group. Using this report, facilitators can move on to a deeper discussion in roundtables.

Development Team and Communication

As a new team formed at the beginning of the semester, we are proud of our teamwork spirit. Our team members have been working on improving our potential, even though for some it might be their first time working as a game designer, programmer, and producer for a semester-long project. Our unified team dynamic leads to extensive collaboration where everyone contributes to a common goal, which is to build a satisfactory product in time from scratch. Even though we assigned one programmer at the beginning, we were able to move roles with flexibility and willingness to speed up the development process. As everyone in the team had programming experience, two game designers later contributed to writing the core algorithms. When we realized that the bucket activity was not working as expected, we didn’t give up and stay with the mediocre version. Instead, we successfully replaced it with the seeking activity with some crunchtime thanks to everyone’s dedication.

Timely communication with the client and instructors has hugely benefited our development because we relied on the fast iteration process to pick an idea or later replace one. Weekly meetings with our client, instructors, and sometimes a combined one allowed us to communicate our ideas, design progress, and problems and receive timely feedback for future iterations. A combined meeting also allowed the client and instructors to talk about different ideas, explain their reasoning, and come down to a final decision in a couple of minutes. This is important because it significantly reduced the risk of going with either idea and later getting rejected by the other, which costs development time and manpower.

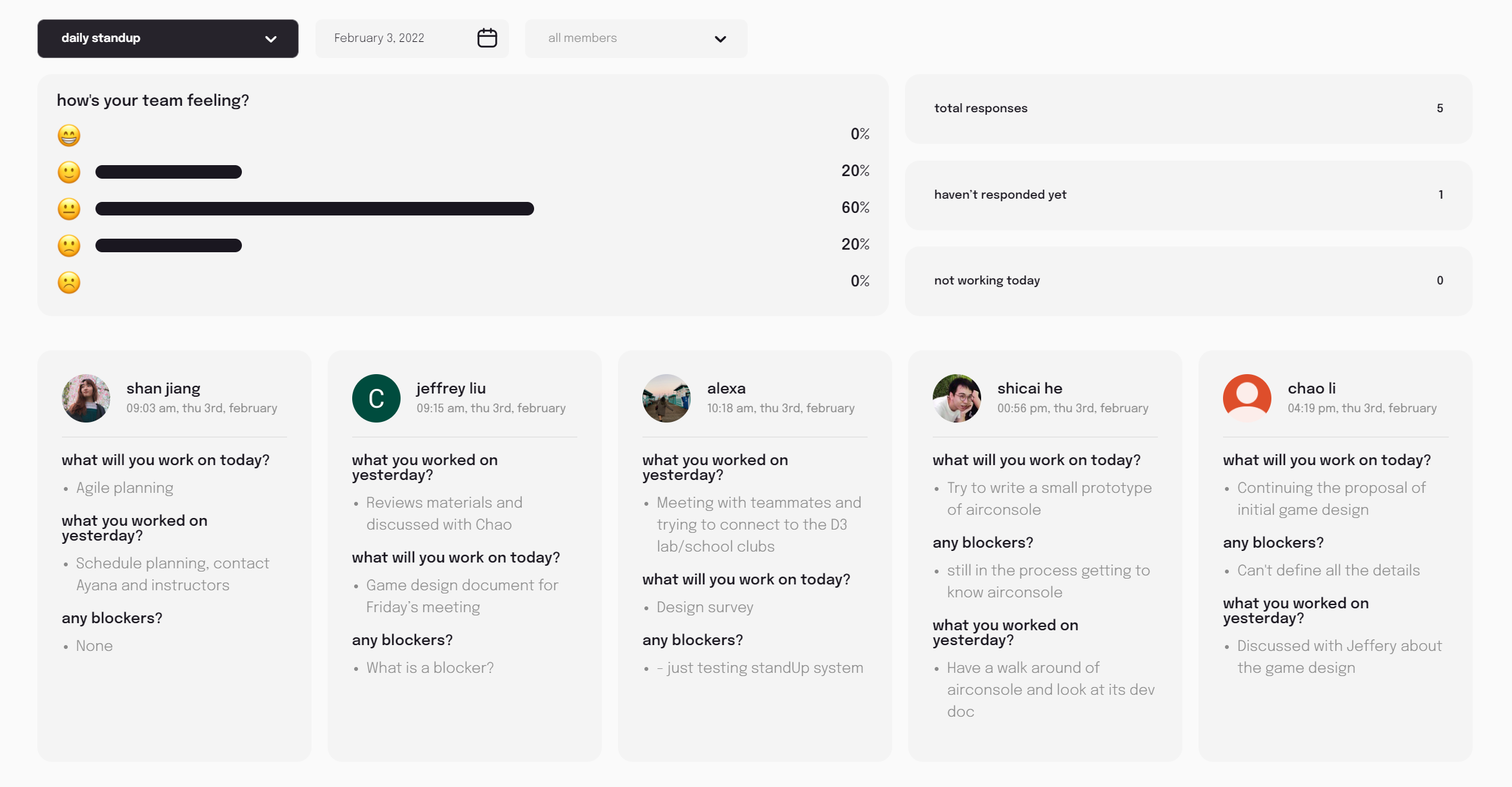

A few project management tools worth mentioning include a shared workspace (Slack) where the team has been actively exchanging information, updates, concerns daily, and an add-on (Sup! Stand-up bot), where daily scrum is automated with the additional feature of a mood tracker. Over the past 15 weeks, we decided that Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays are our core hours, where we dedicate around 25 hours to the project because Tuesdays and Thursdays tend to be busy for elective courses. Although we only had three official days in a week, it worked better than splitting up shorter slots into five days. Everyone has the flexibility to work in the project room or remote although most meetings are encouraged to be in-person. That way, everyone could decide how they would like to balance life, project, and the other elective course.

Slack Workspace

Sup! Standup bot

Playtest, consultation, and feedback

During the development process, we ran more than twelve group and individual playtest sessions with students, faculty, staff, and outside guests, and two consultation sessions with subject matter experts with over 100 participants. These sessions helped us identify problems in game design, server capacity, audience engagement, and facilitation where we later managed to improve the situation.

When our pre-production was mid-way through but still needed help to get a clear picture of what we should be creating for the next 3 months, we had a chance to present to the D3 Lab to gather more feedback thanks to our client. D3 Lab, in full, is the Data-Driven Diversity Lab from CMU, where our client is one of their partners and collaborators. The mission of D3 Lab is to “use data to understand and improve how different groups experience student success, thriving, and sense of belonging at Carnegie Mellon University” and one of their goals is to “identify and understand the experiences of students from a diverse set of backgrounds on campus and analyze existing institutional data to identify areas for improvement”. We believed that with their professional experiences, they could help us realize more pros and cons of the current game designs and where we could focus on in the future. They helped us realize issues in privacy and the necessity to not miss the richness of cultural identity. As students might not be comfortable being with others and sharing personal information during their first orientation, we added the option to keep their identity invisible to others and kept each wheel anonymous. With our current design, while exploring with their wheel in the group space, they could see both the similarities and differences they share with each other.

One of the most critical playtests was the ETC Playtest Day (Week 10), as our first test with over 10 participants which exposed our server capacity issue. This will be discussed again later in the section “What could have been better” because we should have identified the problem before the playtest. During the ETC Playtest Day, we each had around 25 participants in the morning and afternoon sessions, however, because of the server capacity, we made a quick decision to divide each session into three sub-groups. As people came to the test room, we split the seating into 3 sub-groups with around 8 in the left, middle, and right and started from the left. We were able to go through the activity with each section. Even though we lost the chance to test 25 at once, we still received helpful feedback from smaller groups.

As mentioned before, our bucket activity was not working as expected in the playtests. After a consultation meeting with Jessica Hammer, we made up our mind to replace the core gameplay in week 12. Thanks to the perseverance of our team, our transition was successful. From this experience, we realized the importance to reach out to professionals when we seem to be stuck. It should not be embarrassing to admit that we sometimes fail and need a hand. Instead, we could fail fast, learn from our mistakes, and move on to make a better product. Together with the help of faculty and staff at ETC (David Culyba, Carl Rosendahl, Brenda Harger, etc), game designers from Simcoach Games, and all of our outside playtesters, we were able to come up with what we have.

What could have been better

Delayed Product Prototyping

The timeline of prototyping was a key aspect we could improve on. Lack of experience working on a public-facing product from start to end resulted in the underestimated importance of the MVP (minimum viable product). The idea of an MVP is to implement the core mechanics of the product without spending too much time and put them to the test before diving in to polish it. However, we didn’t have a version of MVP at the end of pre-production to gather the audience feedback before we go into full production. Technically speaking, we never had an MVP. Although we had a walkthrough demo through Figma, we did not have a playable version or invite any outside guests to playtest. The earliest playtest with paper prototypes happened in week 6, which was almost semester half. However, even then we playtested to see what minor things we could add or change to improve gameplay, without realizing the core gameplay could be the problem later. The lack of MVP and early playtesting resulted in the realization that our gameplay was not working until Week 10. We hesitated to replace the gameplay for two weeks but eventually decided to in the remaining weeks. Luckily we made it but it could have been much earlier in the development process.

Overall, two weeks of the concept phase and three weeks of pre-production was reasonable considering the first two weeks were remote due to the campus COVID policy. Instead of spending two weeks of pre-production discussing game ideas in illustration and reviewing semantics, we could have built paper prototypes earlier and brought outside guests into playtesting from week 4. Similarly, when we started implementing the digital version, we focused too much time on “building the culture wheel” instead of the true core gameplay – the bucket activity (at the time). We only achieved the full mobile gameplay in week 11 (in total we had week 15), which inevitably led to identifying problems too late in the process. What we could have done was to have a survey with one question, one importance ranking, the full bucket/seeking activity, and one aspect in the report.

During the iteration process, we constantly ignored the big screen, what facilitators should say, and paid most attention to the design of the mobile screen. It should not be the case if we did the project again because the first two are essential parts of the process and lack of them would lead to ineffective engagement and inaccurate feedback of the whole experience. We had to crunch for the last three 3 weeks of the semester to make up for our earlier mistakes. In general, we practiced a Waterfall + Agile framework, with more focus on Waterfall at first. To better structure the development process, we should utilize Agile more considering the project is not really defined in the first place and need fast prototyping to test feasibility. Another reason to use Agile more will be explained in the next section because Waterfall is not recommended to create fun games.

Game engagement and Fun

Transformational games could also be fun, or they need to at least be somewhat fun to keep the audience. Fun was never our priority in the design process until we realized players did not want to keep playing the activity because it was boring. In the Transformational Framework workshop early in the semester, we learned about why it’s important to transform players, how players should be different after playing, how to measure the game’s impact, etc., but not how to engage the audience in the game. We did not balance the educational aspect and the fun aspect because of the nature of cultural humility. It is a serious social topic but to gamify it and engage hundreds of students, we need to add a little spice. We are glad that we replaced the core gameplay with the seeking activity and “killed the baby” although we spent around 4 weeks implementing the bucket activity. We discarded the old art assets, UI layout, and hundreds of lines of code just to make it fun to play. If we couldn’t keep the audience engaged, it would be meaningless to do it, let alone have a deeper discussion afterward.

Quality Assurance

Quality assurance is also a key aspect that we should have paid attention to. During the semester, our instructors and client acted as the QA team in some ways, but we should have dedicated someone to check the overall quality of the product weekly, including UI, art assets, server capacity, mobile compatibility, etc.

Once the UI and art assets are designed, we could have tested them in Figma without any actual implementation in code within the team and outside. Each iteration could be tested separately from the playable version to identify the problems of too many texts, the lack of touch feedback, etc.

Intro Page – Before

Intro Page – After

When the core mechanism is implemented, we should have tested it at scale around halves – 3 weeks before the ETC Playtest Day – to check the server capacity. The bot system should be brought in as a regular testing tool to ensure basic functionality and optimization. Modularity and comments are also important in the early stage of programming, when we need to iterate a lot of times and for future reference.

The responsive interface is another important aspect when dealing with web applications because of the wide range of phones, tablets, and computers on the market. One aspect ratio or dimension hard-coded into the program simply will not suffice. Although responsive interfaces could be hard to test for, efforts must be made to implement and test them. We didn’t treat it as important in our UI design and implementation at first but tried to solve the responsiveness in the last two weeks.

Conclusion

The product has been released online via Github. The program guide and video demo are available for download and viewing to understand the product better. We are excited to see it debut at Dietrich’s Orientation in the fall and possibly expand its use to ETC and other places. Some team members will support the launch onsite to troubleshoot.